The Best of Benedict Evans

20+ most popular Benedict Evans articles, as voted by our community.

Benedict Evans on Apple

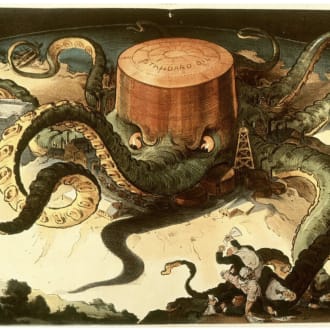

Would breaking up 'big tech' work? What would? — Benedict Evans

We’re clearly going to be arguing about the size, power and market share of large technology companies a great deal in the next couple of years. Many of the underlying concerns we have around…

Benedict Evans on Artificial Intelligence

AI and the automation of work — Benedict Evans

ChatGPT and generative AI will change how we work, but how different is this to all the other waves of automation of the last 200 years? What does it mean for employment? Disruption? Coal consumption?

The problem of AI ethics — Benedict Evans

Can you write laws, or lay down ethical principles, for a technology that will be used in entirely different ways, for different purposes, in different industries? What does that mean if it’s changing…

Benedict Evans on Ecommerce

The end of the beginning

Close to three quarters of all the adults on earth now have a smartphone, and most of the rest will get one in the next few years. However, the use of this connectivity is still only just beginning. Ecommerce is still only a small fraction of retail spending, and many other areas that will be transf

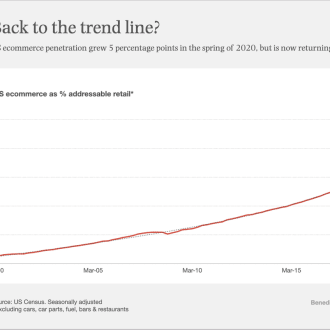

Back to the trend line? — Benedict Evans

The Covid Rotation turns, and ecommerce penetration is back to the trend line. But which trend line, and which penetration?

Benedict Evans on Gadgets

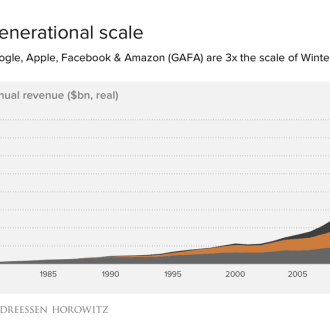

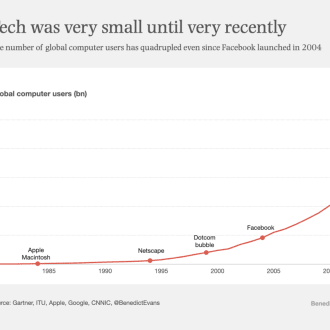

The scale of tech winners

We all know, I think, that there are now far more smartphones than PCs, and we all know that there are far more people online now than there used to be, and we also, I think, mostly know that big tech…

Benedict Evans on Metaverse

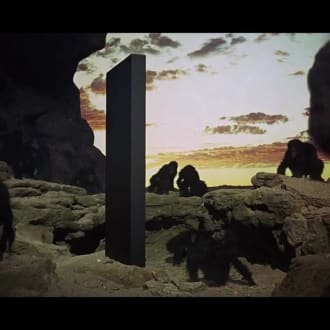

Metaverse! Metaverse? Metaverse!! — Benedict Evans

“Metaverse’ is the buzzword of the moment, yet it doesn’t really exist as more than a label on a whiteboard, and many of the ideas it tries to combine might not happen, or not like that. This might be…

«history teaches us nothing except that something will happen.»

Ways to think about a metaverse — Benedict Evans

Your boss wants a metaverse strategy, but what would that be, and what does metaverse even mean? If we strip away the noise, what can we say about this, and what can we predict?

Benedict Evans on Microsoft

How to lose a monopoly: Microsoft, IBM and anti-trust

A big rich company, a company that dominates the market for its product, and a company that dominates the broader tech industry are three quite different things. Market cap isn’t power. IBM ruled…

Benedict Evans on NLP

Voice and the uncanny valley of AI

WHAT DO WE WANT? Natural language processing! WHEN DO WE WANT IT? Sorry, when do we want what? — Benedict Evans (@BenedictEvans) January 22, 2017 Voice is a Big Deal in tech this year. Amazon has probably sold 10m Echos, you couldn't move for Alexa partnerships at CES,

Benedict Evans on Retail

Retail, search and Amazon’s $40bn ‘advertising’ business — Benedict Evans

Amazon sold close to $40bn of advertising last year - bigger than Prime, bigger than the entire global newspaper industry and probably more profitable than AWS. But is this really advertising, rent,…

Benedict Evans on Technology

The end of the American internet — Benedict Evans

For its first two decades, the consumer internet was American - American companies, products, attitudes and laws set the agenda. That’s not so true anymore - there are more smartphones in China than…

The VR winter — Benedict Evans

“Our vision is that VR / AR will be the next major computing platform after mobile in about 10 years. It can be even more ubiquitous than mobile - especially once we reach AR - since you can have it…

Benedict Evans on Venture Capital

Presentations — Benedict Evans

Presentations by Benedict Evans: Standing on the Shoulders of Giants, The End of the Beginning and Mobile is Eating the world.

Mobile is eating the world

As we pass 2.5bn smartphones on earth and head towards 5bn, and mobile moves from creation to deployment, the questions change. What's the state of the smartphone, machine learning and 'GAFA', and what can we build as we stand on the shoulders of giants?

Popular

These are some all-time favorites with Refind users.

Ways to think about machine learning

We're now four or five years into the current explosion of machine learning, and pretty much everyone has heard of it, and every big company is working on projects around ‘AI’. We know this is a Next Big Thing. I don't think, though, that we yet have a settled sense of quite what machine learning -

Regulating technology — Benedict Evans

We regulate lots of industries, from food to banking to airlines, and now, increasingly, we’re going to regulate tech. But that means global platforms collide with local regulators, with complexity,…

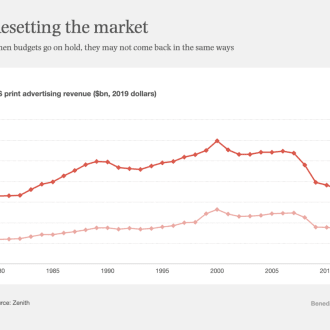

COVID and cascading collapses — Benedict Evans

I’ve been looking at this chart a lot over the past few weeks.

Asking the wrong questions

With fundamental technology change, we don't so much get our predictions wrong as make predictions about the wrong things.

Not even wrong - ways to dismiss technology

How do we get beyond 'that's a toy!' and 'but everything looked like a toy!', and try actually to understand whether a new technology might matter? What are valid lines of reasoning, and what statements are 'not even wrong'?

What is Refind?

Every day Refind picks the most relevant links from around the web for you. is one of more than 10k sources we monitor.

How does Refind curate?

It’s a mix of human and algorithmic curation, following a number of steps:

- We monitor 10k+ sources and 1k+ thought leaders on hundreds of topics—publications, blogs, news sites, newsletters, Substack, Medium, Twitter, etc.

- In addition, our users save links from around the web using our Save buttons and our extensions.

- Our algorithm processes 100k+ new links every day and uses external signals to find the most relevant ones, focusing on timeless pieces.

- Our community of active users gets the most relevant links every day, tailored to their interests. They provide feedback via implicit and explicit signals: open, read, listen, share, mark as read, read later, «More/less like this», etc.

- Our algorithm uses these internal signals to refine the selection.

- In addition, we have expert curators who manually curate niche topics.

The result: lists of the best and most useful articles on hundreds of topics.

How does Refind detect «timeless» pieces?

We focus on pieces with long shelf-lives—not news. We determine «timelessness» via a number of metrics, for example, the consumption pattern of links over time.

How many sources does Refind monitor?

We monitor 10k+ content sources on hundreds of topics—publications, blogs, news sites, newsletters, Substack, Medium, Twitter, etc.

Can I submit a link?

Indirectly, by using Refind and saving links from outside (e.g., via our extensions).

How can I report a problem?

When you’re logged-in, you can flag any link via the «More» (...) menu. You can also report problems via email to hello@refind.com

Who uses Refind?

450k+ smart people start their day with Refind. To learn something new. To get inspired. To move forward. Our apps have a 4.9/5 rating.

Is Refind free?

Yes, it’s free!

How can I sign up?

Head over to our homepage and sign up by email or with your Twitter or Google account.